![]() Kenya is a beautiful country in eastern Africa, considered one of the fastest developing states of this region. In fact, the number of skyscrapers and traffic jams is not far from those of large Western cities. The national parks of Kenya are famous all over the world, and this is where European and American travelers come to see the wild African animals on safari. But if you leave the asphalt highways you will find yourself in an entirely different world. The Russian journalist Denis Makhanko spent some time in one of the poorest regions of Kenya, and learned that Orthodox Christianity, which played a significant role in the formation of modern Kenya, is still a driving force here, and is in part the only hope for the local people.

Kenya is a beautiful country in eastern Africa, considered one of the fastest developing states of this region. In fact, the number of skyscrapers and traffic jams is not far from those of large Western cities. The national parks of Kenya are famous all over the world, and this is where European and American travelers come to see the wild African animals on safari. But if you leave the asphalt highways you will find yourself in an entirely different world. The Russian journalist Denis Makhanko spent some time in one of the poorest regions of Kenya, and learned that Orthodox Christianity, which played a significant role in the formation of modern Kenya, is still a driving force here, and is in part the only hope for the local people.

* * *

The seeds of the Orthodox Faith in this country were planted at the beginning of the twentieth century by Greek immigrants. However, the desire to make Orthodoxy the religion of the Kenyans did not come from the Greeks who held their traditions sacred, but from local people, who like the Russian Prince Vladimir, sought the true faith.

An entire movement arose amongst representatives of the African Kikuyu people in opposition to Western missionaries, who in introducing Christianity also did violence to the folk traditions of the local population. The Kikuyu boycotted the missionary projects of Western Christians, and strove to find a faith in Christ that was not bound up with colonial wars against the local population.

During the 1930’s, the Kikuyu leaders in Kenya invited an Orthodox bishop from South Africa named Alexander Danil. He founded the first churches there, taught Orthodoxy to the people, and ordained priests. Bishop Alexander Danil, an African native and former Anglican priest, had received his ordination in a non-canonical Church, and therefore the first Kikuyu communities did not have any contact with world Orthodoxy.

Finally, in 1946 the Orthodox Kenyans were received under the omophorion of the Patriarchate of Alexandria, but in 1950 the Orthodox Church in Kenya was outlawed—the English authorities associated Orthodoxy with the Mau-Mau uprising.

![]()

The caves along the Tana River of Central Kenya became the refuge for freedom fighters, many of whom were Orthodox Christians, persecuted by the colonial authorities.

Persecution of the Church ceased in 1963 with the country’s long-awaited independence. The first president and Kenyan national hero, Mzee Jomo Kenyatta, had special sympathy for the Orthodox persecuted by the colonists. During the period of struggle for independence, Mzee Jomo Kenyatta was in prison, where he met Orthodox priests. Another fighter for his country’s independence, the future bishop and president of Cyprus, Makarios III, who had been exiled by the British authorities to the Seychelles Islands, made a particular impression upon the future leader of Kenya. After Kenya’s declaration of independence, the Cypriot Archbishop came to that country and baptized thousands of people.

![]()

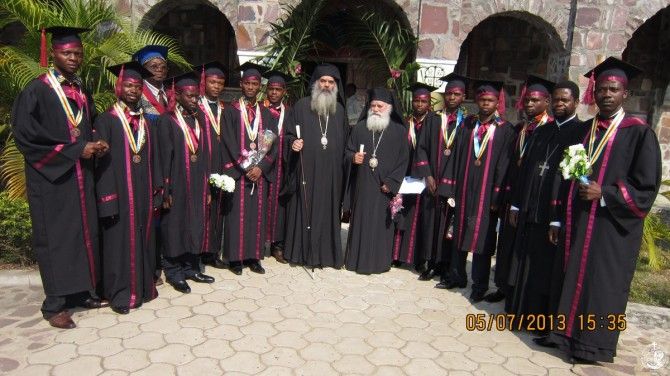

Today in Kenya there are around 620,000 Orthodox laypeople, 260 priests, and one bishop—Metropolitan Makarios. In the Nieri region, which I visited in October, 2011, there are fourteen Orthodox priests serving. I had the opportunity to meet with twelve of them. They are all native Kenyans, and have all studied at the Orthodox seminary in Nairobi.

Climbing into two old automobiles (in the Nieri region, only two of the priests have cars, and it took donations from all over the world to buy them), we set off together for a tour of Orthodox places in the region. There is an Orthodox church in practically every village, and the local people have strong Orthodox traditions.

![]()

The oldest priest of the area, Archpriest Peter Kiniya Vashira, still remembers the mission of bishop Alexander Danil. Fr. Peter is over seventy, and has been serving in the priestly rank since 1970. The most respected and distinguished priest in these parts, he has the duty of father confessor. According to the Greek tradition, the Kenyan Orthodox confess no more than once a month. Confession should be heard by an experienced priest who has been specially appointed for this sacrament.

Fr. Peter serves in a shed equipped as a church on the edge of the city of Karatina. The community rents it from the municipality, paying every month for its use.

![]()

Archpriest Peter

In the village the situation is a little easier with regard to land, but people there have no money at all. During any given church service all the electrical outlets are busy—the parishioners who come to church on Sunday use the opportunity to recharge their mobile phones, because most of their homes have no electricity.

In this situation, the priests and church wardens are ceaselessly occupied with building and repair of parish buildings. The church of the Holy Apostle Phillip is currently being remodeled, and the faithful are gathering at a temporary building made of sticks and branches. The church itself is built from hand-made clay blocks. In the church of the Holy Apostle Paul, cosmetic repairs are being made. The church of St. Nicholas is located in a building that earlier housed a store. This was a great find—the stone walls of the building, which is situated on the top of a hill, protect the church from wind and rain.

![]()

The parishioners meet their guests very cordially. Without any prior agreement, they all chime, “We love guests!” After the traditional Kenyan singing, the faithful all clap their hands to the beat of the drums and perform their unique singing and dancing. The activities of the Kenyan Orthodox are not limited to church services. There are particular efforts made here to create schools. There are few Orthodox schools in the area. The most developed of these is a high school in Ngoru. The three-story building of this school, encompassed by a tall, stone fence (an unheard of luxury for this region), is immediately noticeable. The school even has a specially equipped chemistry and biology lab.

The secret to such growth lies in the fact that the church was built on money donated by the Orthodox Church of Finland—a picture of a snow-blanketed forest hanging by the entrance is a reminder of this. Any organization or private individual can build a school in Kenya. If all the norms and license requirements are fulfilled, the school’s founder can transfer it to the state. This is what the Orthodox Finns did. Now the institution’s operating costs and the teachers’ pay are the government’s concern. But the school is still called an Orthodox school.

![]()

The school uniform and textbooks are a mandatory aspect of a Kenyan school. As a rule, the participants themselves pay for them. Moreover, the children’s thirst for learning is just amazing—the school day continues from morning to evening, and many students walk several kilometers to and from school. The nursery school and elementary school at the church of St. Nicodemos were opened thanks to help from the Orthodox people of Greece. The school’s principal proudly demonstrates his notebook computer—a gift of the Greek benefactors. The children are sometimes allowed to work on it as a reward for diligent studying. In one of the classes we see a map of the world on the wall, and one pupil easily finds Russia on it for us.

Earlier there was a medical station at the church, where anyone could go for help, but it is now closed—there are no funds to support a doctor or to buy medicines.

We are drinking tea and milk with the priests of Nieri. They ask many questions about Russia and tell us about their needs and problems.

One problem is vestments for the priests—something considered an inconceivable luxury here. Vestments are given to priests at their ordination and they are used for ten–fifteen years. When the vestments wear out entirely, the priest makes a request to the metropolitan for a replacement. The Kenyan altar boys also lack sticharions, and there are traditionally many altar boys in the local churches. Sticharions are re-sewn and passed along to future generations of altar boys.

Pectoral crosses are a great rarity. As in Greece, not all priest wear crosses, but only those who have been awarded the right. And they not only have to deserve it—they have to literally make it using a cheap Chinese chain and key rings.

![]()

But anyway, the priest’s cross is not the main thing, say the priests. Much more needed are baptismal crosses for the parishioners. Neither the local parishes, nor the faithful themselves are able to afford them. “And after all, the baptismal cross is a visible sign of our faith! One can’t do without it!”

Having arrived at the Kenyan lands only a few decades ago, the Orthodox Church is growing dynamically in this country. Enlightenment of the people, prayer, help for the needy—the Orthodox churches and schools are becoming the center of life in rural areas. On the seal of Kenya is the word, “Narambee”, which means, "Let us all pull together". Life in the Orthodox Church is in accord with this motto. Here everything is done together, in council, sharing each others’ joys and hard times, problems and victories.

I would like to believe that Orthodoxy is the future of Kenya, and maybe even all of Africa. The Orthodox Church has a chance here to become not only one of the many Christian confessions represented in the country, but the motivating force that gathers people together, and makes them better. The Kenyan priests do very much to make this happen; however their possibilities are limited. But each one of us can help if only by telling our friends about this service.

Denis Makhanko, translation by OrthoChristian.com

Since a young child I have had great interest in the spreading of the gospel. One of my earliest memories was seeing my grandmother praying twice every day for missionaries all over the world. Everything in my life has been colored by this desire. As a Byzantine Franciscan, I thought one day I would go behind the "iron curtain". As a public school Guidance Counselor for 28 years I viewed my work as missionary work. In 1992 my family, with one other family, began a Mission Station in our living room. We outgrew two storefronts and now have a beautiful church in Southbury Ct. In 2007 when our children were grown my wife, M. Suzanne and I answered the call from OCMC to lead the first mission outreach to the Turkana people of Kenya. We helped them build their first church. Since then we have returned in 2010 preaching and teaching in the most isolated areas of Turkana and in 2011 conducting Catechist training and teaching. In 2012 we led a group to a very isolated area of Turkana to build a second church. These beautiful, and very isolated people, have become a vital part of our lives. With great enthusiasm we want to share their lives and their message to all in America.

Since a young child I have had great interest in the spreading of the gospel. One of my earliest memories was seeing my grandmother praying twice every day for missionaries all over the world. Everything in my life has been colored by this desire. As a Byzantine Franciscan, I thought one day I would go behind the "iron curtain". As a public school Guidance Counselor for 28 years I viewed my work as missionary work. In 1992 my family, with one other family, began a Mission Station in our living room. We outgrew two storefronts and now have a beautiful church in Southbury Ct. In 2007 when our children were grown my wife, M. Suzanne and I answered the call from OCMC to lead the first mission outreach to the Turkana people of Kenya. We helped them build their first church. Since then we have returned in 2010 preaching and teaching in the most isolated areas of Turkana and in 2011 conducting Catechist training and teaching. In 2012 we led a group to a very isolated area of Turkana to build a second church. These beautiful, and very isolated people, have become a vital part of our lives. With great enthusiasm we want to share their lives and their message to all in America.